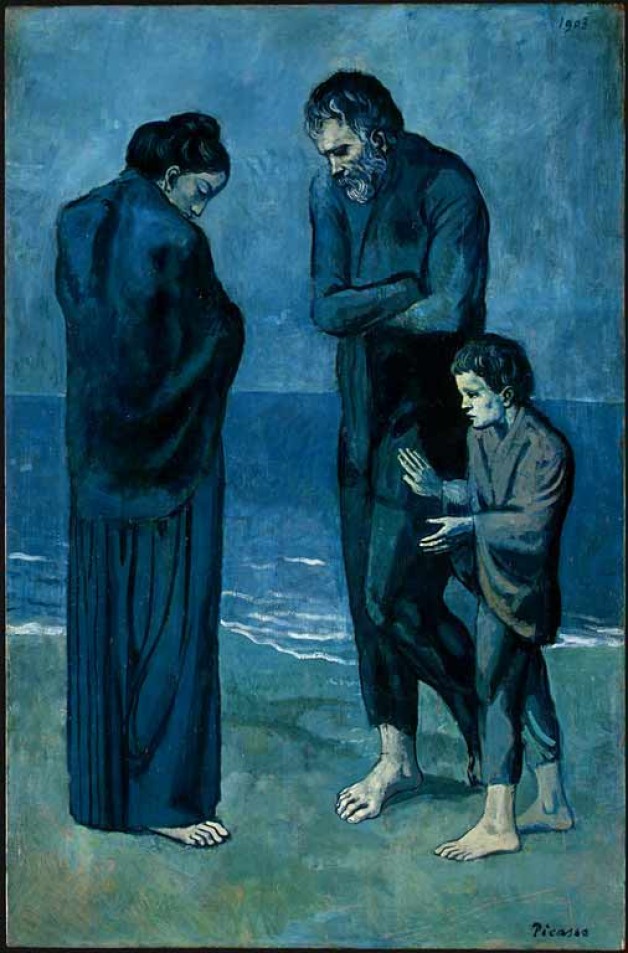

Pablo Picasso’s Tragedy (1903) depicts three figures huddled on a beach – presumably a family. We see nothing of the ‘tragedy’ itself, however; no trace of specific disaster remains, and we are left to speculate about what series of events may have led to their misfortune. The focus of the painting centers us on the figures themselves.

The man and woman are turned inwards in an inherently familial pose, but the distance between them and their downcast eyes reveal their inability to comfort each other. The child, too young to understand the meaning of his own experience, places a hand on the man and looks pleadingly in the direction of the woman. Neither have anything to offer him, and this feeling of impotence must only increase their own suffering. Here ‘tragedy’ functions as a subject in the painting not in reference to any single event, but simply as the human experience.

Picasso is not alone in choosing to depict forms of human suffering and loss, and there is something fitting about this. Even after the fall, it seems that art is still inclined towards a kind of imitation of nature. Good art resonates with our experience of the natural world and with our own human nature as well. It does not flinch in the presence of failure, personal weakness, or moral evil. In point of fact, what is often so disedifying about pseudo-art or kitsch is not so much its technical mediocrity as its lack of honesty. Of course, an undifferentiated portrayal of negative experience can also lead to an insufficient humanism or naturalism. Worse still would be a deliberate focus on ugliness. The seeming danger for Picasso is not the first of these pitfalls, but the latter two.

The subject of Picasso’s work is something that should be inherently undesirable. There is nothing beautiful about tragedy. Although we may be slow to say so, the sight of others’ suffering has the power to repulse and to send us searching for a distraction. Nonetheless, there is something intuitively beautiful about Picasso’s Tragedy that strikes us as paradoxical only on second thought. The painting seems to exert an immediate draw that transports us directly onto Picasso’s gray-blue beach, bringing us close to the figures and to their nameless tragedy as well; it is only on further reflection that we realize how strange it is to be attracted by something so plainly awful.

Picasso draws our attention directly and simply to their pain itself, with no outside referent to distract or to offer impartial resolutions. When considered critically, there seems to be nothing attractive about this. And yet Picasso has presented tragedy simpliciter, and we are drawn by it not as we might be by a depiction of pleasant scenery, but as a father might be drawn by the suffering of his son. Picasso has portrayed the human experience of tragedy in such a way that we feel no revulsion – no burning need to distract ourselves from the human suffering before us. Tragedy is here framed in such primary and universal terms that it necessarily resonates with us all, evoking not pious sympathy, but real empathy.

The presence of beauty in a painting like this will always remain somewhat elusive, but perhaps a trace of an explanation can be found in Picasso’s authentic humanism. Picasso manages to elicit that which is most human in each of us by drawing us into another’s experience of something with which we ourselves are only too familiar.

Picasso was not a religious man, and there is no hint of theological horizon present here. His secularism extended even to his parents, who did not raise him as a practicing Catholic. And yet in spite of this, his work seems to be open to something greater. Perhaps it was the cultural Catholicism of his native Spain which imbued him with a certain anthropological honesty that was receptive to the motions of grace, if only subliminally.

Tragedy in the natural sense is survivable; no misfortune, however great, can completely discourage a person from seeking the good. But God alone can undo the knot of tragedy itself, reestablishing us in the newness of grace. Perhaps Picasso would not have anticipated it, but when his Tragedy is viewed in faith, our natural empathy takes on a supernatural character, and one desires to speak the words of Christ to those figures on the beach: “If you knew the gift of God… you would ask him, and he would give you living water.”

Image: Pablo Picasso, Tragedy