In a recent post, Br. Justin Hannegan, a monk of St. Louis Abbey, proposes an explanation for the radically declining number of vocations to religious life over the past half century. On Hannegan’s reading, the source of the problem lies in an overemphasis on following the desires of one’s heart as opposed to presenting, in all of its stark rigor, the arduousness of the religious ideal as an objectively higher and therefore more securely salvific way of life. Although I may be oversimplifying his argument, I understand him to claim that because religious life involves a more thoroughgoing renunciation of our inborn inclinations (to marriage, possessions, independence, etc.), it provides the intrepid soul with an objectively better regimen for spiritual growth. If this were preached, he argues, we could expect to see an increase in vocations to religious communities. Because it is not, he adds, it is no surprise that we find men and women “spurning religious life” and choosing marriage as more in keeping with their inborn desires.

I think that Br. Justin has made a number of good points, though I’d like to suggest an alternative approach to religious life that contextualizes and, I think, shows the merit of the language he finds destructive.

In my own experience, the starkness of the religious ideal had a part to play in my joining the Dominicans. Looking back on time spent in college, I experienced some of the fatigue which comes of dividing one’s efforts. I enjoyed the gift of many good things in school: a supportive community, faithful friends, engaging studies, and good professors; and yet, I remained somewhat torn by the experience of dispersion. While I tried to apportion myself among all the people, studies, and worthy pursuits which surrounded me, I was unable to give wholly of myself. In this context, religious life represented the hope of a unified and whole-hearted existence for the one thing necessary.

I think it is only in this context that the discipline and renunciation about which Br. Justin speaks appear attractive and worthy of pursuit. I do not think that man is capable of choosing “death” simply. In order to choose something, it must first appear to us as in some way attractive—it must draw us, it must allure us. The object must strike us as worthy of pursuit or else it will pass under our noses – neutral, unimportant, and otherwise unworthy of note. Whenever we choose something, be it a new toothpaste or a new barber, we choose it as promising some good, some happiness, either in itself or leading to a further good. For religious this good—the good that leaps off the page, that confronts us with urgency, that merits a response—is the worship of God.

Religious life takes its name from the virtue of religion that orders man’s worship of God. St. Thomas Aquinas explains that each virtue responds to a certain reality in the world and works to perfect man so he can live best in relation to that thing. The classic example is temperance. Temperance responds to the presence of sensible pleasures (particularly of food, drink, and sexual intercourse) and works to perfect man that he might pursue these goods in accord with right reason and the divine law. The virtue of religion rightly orders our relationship to God, to whom we owe all praise since he has created us and even now sustains us in being. In order to “repay” this debt, to respond as best we can to our Creator, we render to him acts of service—St. Thomas mentions adoration, sacrifice, prayer, devotion, etc. Now religion is a virtue to be cultivated by all men and women, but in a peculiar way by religious: “Although the name ‘religious’ may be given to all in general who worship God, yet in a special way religious are those who consecrate their whole life to the Divine worship, by withdrawing from human affairs…” (Summa Theologiae IIaIIae, Q. 81, a. 1). Here we find the context for Br. Justin’s insistence on the renunciation and arduousness of religious life – they are strictures chosen in view of the further good of religion.

From the vantage of virtue, religious life truly is a desirable good and a beautiful call, and one born of seeking relation with God. While, as Br. Justin accurately points out, there are renunciations that accompany the call to religious life, they can only be sustained for love of Jesus and for the worship of God, which St. Thomas identifies with the sanctification of the human heart. Note that this is different from choosing religious life because it is higher and more “proven” to engender sanctity, which fails to capture the rich interpersonal dimension that a virtue-based approach accentuates. The life of religious is ultimately an oblation of love. The way is arduous, but not without joy, for He is delightful!

I believe it is for this reason that vocation directors, counselors, and authors may rightly insist upon the legitimate place of desire in discernment. The seed of the love that blossoms in the worship of God can be found in the God-given desires of our hearts. Granted, this is complicated by sin and the self-deception born of the egotism that seeks to undermine our pursuits, but I do not think that it requires abandoning the language of desire. While our desires remain capable of manipulation and in need of direction, by the grace of God, our desires continue to speak in us the faint but persistent invitation of vocation.

✠

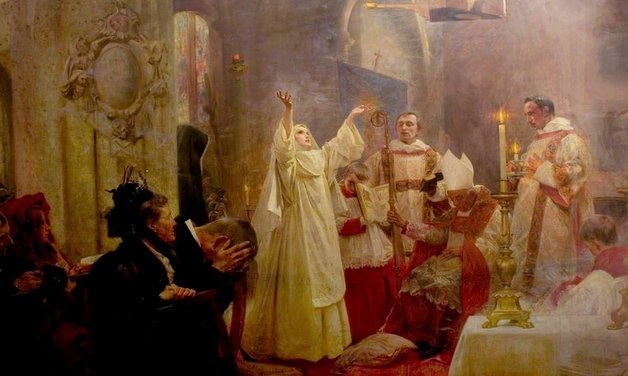

Image: John Henry Frederick Bacon, Suscipe Me, Domine