Your hair is straight and dark, and your skin is very fair. I suppose you’re not prettier than most children. You’re just a nice-looking boy, a bit slight, well scrubbed and well mannered. All that is fine, but it’s your existence I love you for, mainly. Existence seems to me now the most remarkable thing that could ever be imagined.

Thus writes John Ames, the main character in Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Gilead. The novel takes the form of a lengthy letter written by Ames, an elderly Iowa pastor who married late in life and, struck with a terminal illness, faces the prospect of leaving behind his wife and young son. In the letter – intended to be read by the son long after his father’s demise – Ames writes the many things he would have liked to impart to his son had illness not intervened.

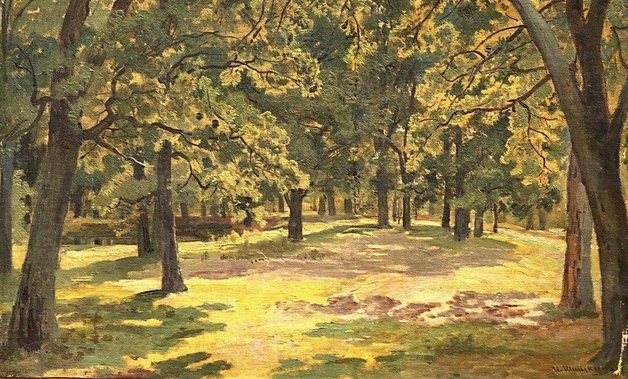

Among the many themes in Robinson’s novel, the sense of awe at the wonder of existence that pervades Ames’s thoughts stands out. At one point he declares, “I have been thinking about existence lately. In fact, I have been so full of admiration for existence that I have hardly been able to enjoy it properly.” What sparks this admiration? A lunar eclipse? A glorious thunderstorm? Nothing of the sort; rather, it is ordinary, everyday objects that move Ames: “I have lived my life on the prairie and a line of oak trees can still astonish me. I feel sometimes as if I were a child who opens its eyes on the world once and sees amazing things it will never know any names for and then has to close its eyes again.” Ames is a character who feels the weight of one of the great philosophical questions: Why is there something rather than nothing?

In a meditation on the commandment to honor father and mother, Ames reflects on how the Lord gives everyone somebody to honor: the child the parent, and the parent the child. He then describes his wife’s love for their son as an embodiment of that honor, in that it reflects the love of God, and from this he concludes: “You see how it is godlike to love the being of someone. Your existence is a delight to us.” This godlike quality is firmly rooted in the first creation account of Genesis: “And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31).

The wonder of existence also lies at the heart of the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. The German philosopher Josef Pieper notes that, whereas St. Augustine emphasizes the essence of God (what God is), for St. Thomas God’s mere existence is fundamental. St. Augustine interprets the divine name of Exodus 3:14 (“I am Who am”) in terms of God’s unchangeable nature; St. Thomas takes the words to signify, “I am the pure act-of-being.” At first glance, this interpretation might seem dry and uninteresting. But if one ponders it more carefully, one can’t help but be struck by a sense of awe. As Pieper notes, “What makes things truly ‘real’ is the act of existing.” But, he adds, only God can call things from non-existence into being, a point St. Thomas illustrates with vivid language:

Because God by virtue of His essence is existence itself, therefore the existence of what he has created is necessarily a producing peculiar to His essence; just as flaming up is the effect peculiar to the essence of fire. (ST I q. 8 a. 1)

Pieper draws out the implications of this teaching: “Wherever we encounter anything real, anything existent in any way whatsoever, we encounter something that has ‘flamed up’ directly from God.” In other words, in encountering everyday, run-of-the-mill things – a line of oak trees, an ordinary son – we in some sense meet the living God. In light of this Pieper offers a modification of the classical philosophical dictum “Everything that is, is good”: “Because the being of the world participates in the divine being which pervades it to its innermost core, the world is not only a good world; it is in a very precise sense holy.”

It is this holiness that drives a character like John Ames to wonder at the sheer fact of existence. That anything other than God should exist is a miracle of sorts. And yet the wonder of St. Thomas and of Robinson’s character does not end in this life – it points to the next. But rather than detracting from the significance of the present world, the prospect of the world to come imbues this world with a far deeper significance. Reflecting on the passing nature of the world and the prospect of the resurrection, Ames writes:

In eternity this world will be Troy, I believe, and all that has passed here will be the epic of the universe, the ballad they sing in the streets. Because I don’t imagine any reality putting this one in the shade entirely, and I think piety forbids me to try.

Christ’s resurrection is the ultimate testament to the goodness of creation, the surest sign of God’s love for a world marked by his holiness. And so, the octave of Easter we observe this week is not just a celebration of Christ’s victory over sin and death; it is also a reminder that, in the words of John Ames, “Existence is the essential thing and the holy thing.”

✠

Image: Ivan Shishkin, Oak Forest